Should We Cancel Halloween? Rethinking School Holidays & Celebrations for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice

Jack-O-Lantern. Photo by Lisa Fotios

Over the past few years, educators across the country who are committed to diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice have been struggling with how to approach holidays like Halloween, Thanksgiving, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, and Christmas, which have long been the foundation of school calendars—particularly the “fun” parts. Their dilemma is how to provide memorable traditions for students and families without excluding, marginalizing, or reinforcing stereotypes about students from different backgrounds. To support schools in thinking through their decision making more clearly, I propose the following four step process: clarify your purpose, identify problems, plan alternatives, and proactively communicate changes.

Step 1: Clarify Your Purpose

The first step in planning any kind of school celebration or event is to align it with your broader school purpose. At Justice Leaders Collaborative we believe that schooling has three purposes:

Purpose 1: To provide a physically and emotionally safe place for children. This means ensuring schools are free of violence, bullying, discrimination, exclusion, and emotional or physical abuse, especially for students who have historically been marginalized, excluded, and targeted in schools (such as students of color, students with disabilities, LGBTQIA students, low-income students, English Language Learners, students who are non-Christian, etc.).

Purpose 2: To prepare students to be responsible participants in a diverse democracy. This means making sure all students feel good about who they are while also learning about others who are different from themselves (commonly referred to as providing students with “mirrors”—reflections of themselves and their own cultures—and exposing them to “windows” into the lives, experiences, and histories of people different than themselves).

Purpose 3: To prepare students to be able to care for themselves, their families, and their communities. This means helping them develop skills such as literacy, numeracy, creativity, critical thinking, and innovation—the things most often discussed when it comes to the goals of schooling.

How schools handle holidays and celebrations (or really anything!) should be considered in connection to these overall goals. We should not continue doing something just because “that’s the way we’ve always done it” if the way we’ve always done it is not aligned with our broader purpose.

If one of your purposes is to provide a safe space for all children, you might ask:

Is this being done in a way that allows everyone to feel a sense of belonging?

Who might be excluded?

Does our approach meet the needs (mental, physical, emotional, language, disability, financial) of all students and families?

Is it racist? sexist? ableist? heterosexist?

Is there a financial burden?

Who is this fun for? Who might it not be fun for? Why not?

If one your purposes is to provide windows and mirrors for all students, you might ask:

For which students does this holiday or event provide mirrors? Are these the same students who usually see themselves reflected in what we do in this school?

For whom does it provide windows? Are these the students who are usually spending their time learning about others?

Are there problematic or inaccurate stereotypes or misinformation being promoted about a group as a result of this celebration, event, or activity?

And if one of your purposes is to provide students with academic skills so that they can care for themselves, their families, and their communities, you might ask:

Does our approach to this holiday help students think more critically?

What new information or new skills are students learning?

Each school and educator may have different purposes. Whatever the case, the first step in trying to align your holidays and celebrations with your commitment to justice, is to attend to why you are doing what you are doing and pay attention to how those decisions are impacting all of the students and families you serve.

Step 2: Identify the Problems

Once you get clear about your purpose, problems with your current practices will become easier to identify. For example, in many schools Halloween celebrations fail to provide a sense of belonging and inclusion for low-income students and families. Teachers regularly tell me stories of students crying in the principal’s office because they feel ashamed of the costumes their families provided, because their parents could not afford to send in a candy treat, or because their parents could not take off work to join the Halloween celebration. In short, Halloween as traditionally done in elementary schools is more “fun” for the students who are the most advantaged—students with families who can afford the fanciest candy and costumes and whose parents have the most flexibility to be present during the school day.

Other commonly celebrated holidays have similar challenges. For example, schools often celebrate Mother’s Day even though many students do not have mothers they are in relationship with (such as students with two fathers, students who are being raised by extended family members, or students in foster care). Other students may have more than one mother but only be allowed to make one gift. Perhaps a student has an abusive or neglectful mother that they do not want to make a special item for, or perhaps a student’s mother has passed away. Mother’s Day inherently excludes many diverse families and is likely only “fun” for those students with traditional family structures with loving supportive mothers.

Thanksgiving is often approached in schools as an opportunity to put on a play about the supposed first meal of the “Pilgrims” and “Indians.” The entire premise of the holiday is historically inaccurate, promotes problematic stereotypes about Indigenous Americans, and often relies on cultural appropriation, such as dressing children in feathered headdresses. Thanksgiving as traditionally done in most U.S. schools undermines our purposes of creating safe spaces free of racism, of exposing non-Indigenous students to “windows” into the true, accurate experiences of Indigenous Americans past and present, and of educating critical thinkers who are continually expanding their knowledge and understanding of the world.

Similarly, schools often focus a lot of energy on Christmas, even though many students do not celebrate the holiday. Moreover, they often do so in ways that reinforce class inequality. The narrative of “Santa” and the Elf on everyone’s shelf is that if you’re “good” you get gifts and if you’re “bad” you do not. The inherent message to students whose families cannot afford to buy them all the things (or who choose not to) is that they must be “bad” kids. Christmas is “fun” for the children who are Christian and whose caregivers have the resources to make Santa come alive.

My guess is that there is work to do when it comes to many of your school’s traditional celebrations.

Step 3: Plan Alternatives

Once you’ve identified the problem, it doesn’t mean you have to simply cancel everything! The next step is to plan alternatives by asking:

Is there something we could change to make this more inclusive of more students and families?

Is there something we could change to provide more mirrors and windows for students who haven’t historically had them?

Is there a way to better align our celebrations with our purpose?

For people who loved traditional school celebrations as a child (or who still do), the idea of change can feel upsetting. But there are ways to make changes that are aligned with our larger purpose, retain fun, and even provide opportunities for new traditions. There are so many possibilities between doing nothing and doing something the way we’ve always done it!

For example, if the purpose of your school’s Halloween festival is to have a fun school-wide event in which everyone feels as sense of inclusion and belonging, and the primary problem is that it reinforces class inequality, there are all sorts of creative solutions:

Have students make masks or create costumes out of recyclable materials at school—perhaps in art class. Imagine a school parade in which everyone is wearing a mask or vest they created themselves rather than one in which the wealthiest students come with the “best” costumes.

Collect donated costumes for all students to pick from, rather than just those whose parents can’t afford one.

Rather than requiring that each family bring a bag of candy, communicate the amount of candy needed for the school overall and ask families to donate as they are able. Some families may be relieved by not having to buy candy, while others will likely be happy to get more! Then instead of individual families being (or feeling) singled out, the school can simply pool all the donations they receive and distribute it equally across classrooms.

Beyond money, maybe there are families in your school who do not celebrate Halloween for religious or other reasons. Rather than their children being excluded, you could plan a Fall Harvest Festival, not one that is a disguise for Halloween, but an authentic opportunity for students to be outside, to taste apples, to do a corn maze, or to learn about and cook the three sister crops of Indigenous Americans—squash, corn, and beans.

Or perhaps you have students with food allergies, or you would actually prefer to not give a building full of students bags full of candy (as a parent myself, I would prefer you didn’t! See the hilarious Halloween episode of Abbott Elementary for more on this). Is there something else that could be passed out as a fun treat? Stickers? Fruit? Silly notes with scary jokes?

The point is, once you identify why a celebration is problematic—maybe it excludes students based on class, race, culture, religion, sexual orientation; relies on or reinforces problematic stereotypes or misinformation; doesn’t foster critical thinking; or it’s only fun for some—there are any number of alternatives you can create.

Step 4: Proactively Communicate

As you transition to events, celebrations, and holidays that are more aligned with diversity, inclusion, and justice, remember the importance of communicating early and often! Pushback often results from the failure of schools to proactively and clearly communicate changes first with staff, then with the broader community. Let students and families know about all the fun exciting things you will be doing this year that seek to provide all students with a sense of belonging. If you’re making a change, explain why and then let people know what you’re doing instead! And do it well in advance! Be prepared to answer some questions, while being clear about your larger purpose.

Conclusion

Creating schools that foster diversity, inclusion, equity, and justice means reconsidering many of the things we have “always done.” This work will not necessarily be easy. And sometimes the “right” answer won’t be clear. But those of us committed to creating a better world, especially for our children, should embrace rethinking school celebrations as an exciting place to start. Good luck!

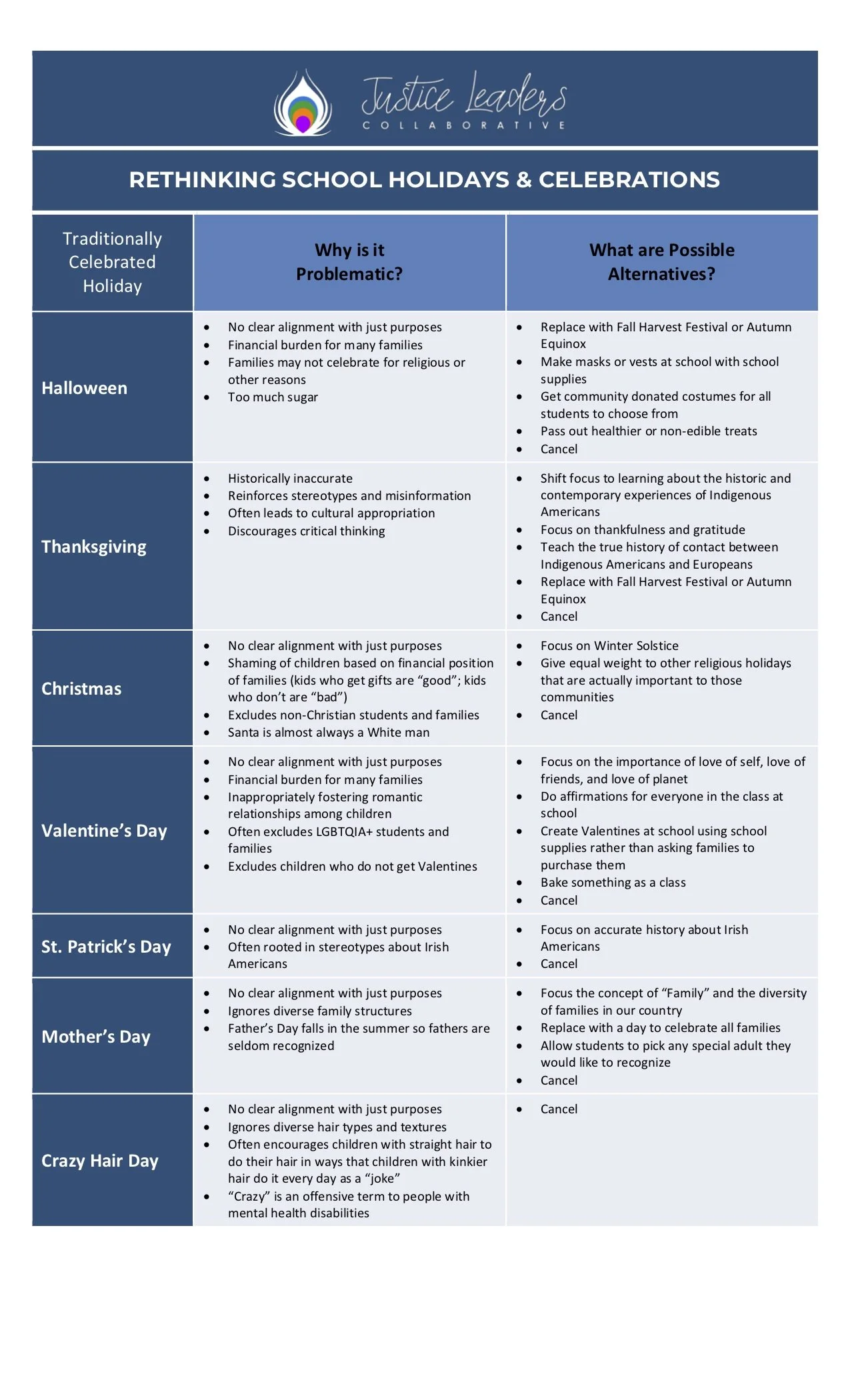

Visit our store to download our free printable worksheet to help you plan and see the chart below to get you started!

Shayla Reese Griffin is the co-founder of Justice Leaders Collaborative and the author of the forthcoming children’s book The Awesome Kids’ Guide to Race illustrated by Christina O.; two adult books, Those Kids, Our Schools: Race and Reform in an American High School and Race Dialogues: A Facilitator’s Guide to Tackling the Elephant in the Classroom; three Justice Assessment & Transformation Tools for k-12 schools (the EJATT, now available for purchase), organizations (the OJATT), and institutions of higher education (the HEJATT); and lots of medium essays & blog posts. She is a mother of 3 and coincidentally tends to get her best ideas around 3am.