What Students Should Be Learning about Race and Other Identities: K-12 Standards for Justice

Justice Leaders Collaborative Standards for Justice Checklist GridEducators, schools, and families across the country are more committed than ever to preparing the children and youth in our care to live and work in a diverse, global society; to making sure all students see themselves in what they learn at school; and to living up to our founding principles of “liberty and justice for all.” However, because K-12 curriculum companies and state standards have not done an adequate job in this area, classroom teachers are all too often left on their own to figure out how to scaffold learning for diversity, equity, and justice—with great fear of backlash from those who do not share this vision.

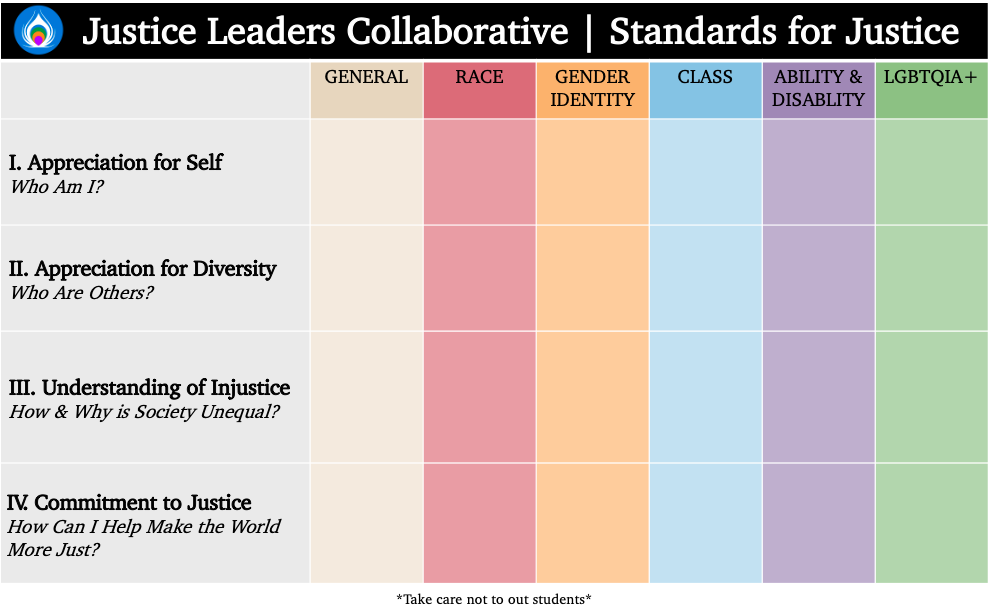

After working with schools and educators for decades on issues of diversity, equity, inclusion, and social justice, our team at Justice Leaders Collaborative has put to paper a set of clear, concise standards for how to approach teaching equity and justice generally, as well as how to specifically address race, class, gender identity, LGBTQIA+ identity, and (dis)ability. It is our hope to provide educators with more support in practically implementing learning for diversity, equity, and justice in their classrooms. These Standards for Justice are aligned with Justice Leaders Collaborative’s broader work, which includes our:

Education Justice Assessment and Transformation Tool (EJATT)–which provides a vision for how we create more just schools by transforming teaching & learning; relationships & climate; behavior & discipline; images, celebrations & events; policies & procedures; and educators’ own knowledge, biases, & beliefs;

A RIDE: Lesson Planning for Social Justice Tool;

Just Books Tracking Tool; and more.

The Standards for Justice are grouped into four broad categories to help educators plan ways for students to develop their:

Appreciation for Self,

Appreciation for Diversity,

Understanding of Injustice, and

Commitment to Justice.

Within this framework, we have also developed specific standards for multiple identities–race, class, gender, LGBTQIA+, and ability and disability. These standards build upon each other to scaffold learning in ways that are developmentally appropriate. We hope educators will use the standards both as they plan individual units and lessons, and as they scaffold learning about diversity and justice over a school year and across grade levels. Below you will find a summary of each of the four categories as well as a link to download the full standards for free.

I. Appreciation for Self | Who Am I?

K-12 schools should be places where young people come to understand and feel good about who they are with regard to the group identities they hold. One of the core fears preyed on by the movement to roll back progress in our democracy and schools is the false claim that talking about issues of social justice will lead White students to “hate themselves.” In fact, the first goal of any good practice related to equity and justice is to help all students feel good about and appreciate who they are, where they are from, and the power they have to make the world a better place by understanding their own identities in broader social and historical context.

For example, all students should:

spend their days in classrooms where they can be their whole selves;

have access to crayons, markers, and construction paper that match their skin color;

be continuously exposed to positive literature that features protagonists who they can identify with and who reflect the diversity of the broader world (see our Just Books Tracking Tool to help you develop your library);

learn about people who have helped make the world a better place who share their backgrounds;

learn about great pre-colonial civilizations in Africa, Asia, and the Americas before learning about colonization, enslavement, and other forms of oppression and inequality;

experience teaching that values the uniqueness of their cultural heritage and traditions as integral to our community, country, and world; and

be provided with the language and tools to understand concepts like “race” and “gender” so that they can locate themselves in the world and understand the impact of systems like “racism” and “sexism.”

II. Appreciation for Diversity | Who Are Others?

After students have come to appreciate themselves and their own identities, the next step in educating students for justice is helping them cultivate an appreciation for those who are different from them in terms of race, class, gender, ability, and other identities. Coming to appreciate yourself and others requires that schools expose students to what Rudine Sims Bishop calls “mirrors” and “windows” — curricula, books, images, and celebrations that show students the significant contributions, histories, and experiences of people both from their own groups (mirrors) and from groups they do not identify with (windows).

Moreover, schools should seek to provide students with opportunities to build meaningful relationships across difference so that they can cultivate a shared sense of community, develop empathy for others, and be prepared for the kinds of collaborative relationships they will need in their broader lives. By starting with helping children and youth come to appreciate themselves and the diversity of others, educators and families are cultivating a strong foundation upon which students can learn about the history and current reality of injustice in our world and how they can play a role in creating positive change.

III. Understanding of Injustice | How & Why is Society Unequal?

In order to create a more equal society, students must develop the critical thinking skills to make sense of the world around them. Specifically, they should come to understand the ways in which our society has been and remains unequal, and why. Unfortunately all too often we educate students in ways that suggest that we live in a country where everyone is treated equally, despite students’ own daily observations and lived realities.

For example, students are likely to observe economic differences between White families and Black families without any prompting from adults. Driving around in a car or riding on a train through various neighborhoods reveals the ways in which racial and economic segregation persist in our country. Or perhaps they’ve noticed gender differences in sports, toys, or even enrollment in courses in their school. Without guidance from knowledgeable, thoughtful adults it would be easy for students to develop (and internalize) biased and bigoted explanations for the differences they witness everyday in their lives, rather than coming to understand how our history, laws, policies, and broader culture have created such inequality through things like redlining and gender discrimination in the STEM fields.

Unfortunately, too many well-meaning educators who want to engage students in these essential conversations start with stories of injustice without laying the foundation of an appreciation for self and others, which risks reinforcing the very narratives that equity and justice efforts seek to interrupt. Because so many educators are pursuing this work without much guidance, most American children are introduced to race (and other identities) through the lens of oppression, especially of Black Americans, with virtually no context, no appreciation, no celebration, and no joy.

For example, schools across the country introduce Kindergarteners to the story of Ruby Bridges — the African American 6-year-old who integrated an all-White elementary school in the face of hatred and vitriol — without having first introduced students to the great civilizations of Africa, the amazing contributions of Black people to early America, or even what “race” actually means (hint: It’s not “skin color.” As children can easily observe, people of the same race can come in many different colors), let alone how Black Americans came to live in the United States, or even why and how the country was segregated! Moreover, we fail to teach anything about what happened to Ruby Bridges and her family after this decision, what happened to educators of color when schools were integrated across the country, who was responsible for doing the “integrating” and why, or what the long-term effects have been. Consider all of the mental leaps children must make to connect the dots of an isolated lesson about Ruby Bridges to the larger society they live in today. Think of all the assumptions children might make about people from different racial groups if they only learn about “race” and “diversity” through the lens of how some groups have been treated badly.

Moreover, oppression, injustice, and inequality are too often discussed in schools as elements of the distant past, rather than ongoing realities. For example, we teach students in our overwhelmingly racially homogenous schools that the Civil Rights Movement ended segregation–a lesson that defies logic! The sort of denial and cognitive dissonance we are cultivating in children who, in too many schools in our country, can look around their own classroom and primarily see only other children who share their racial identity, is irresponsible and does not provide them with the tools to make sense of our society.

In contrast, helping students cultivate an understanding of injustice prompts them to think critically about why — even after the gains of the Civil Rights Movement — so many of our classrooms remain so racially homogenous. We must recognize and think critically and truthfully about the ways in which our society has been and continues to be unequal in order to fulfill our moral and ethical duty to do everything we can to ensure all people are treated fairly, with humanity and justice.

IV. Commitment to Justice | How Can I Help Make the World More Just?

The final group of standards are about helping students commit to making the world a place where a person’s race, class, gender, ability status, or LGBTQIA+ identity are not correlated with the opportunities you have access to, the resources available to you, or how you are treated in our society.

The ultimate goal of teaching for justice is one most Americans agree with — to create a society in which we can celebrate and appreciate our differences without them being connected to inequality. But achieving this goal will require a lot of work! It will require that students learn what a just society would look like, that they develop skills for interrupting bias in themselves and others, and that they get to practice the many ways they can take action in their spheres of influence to make the world a better place–in part by learning how others like them have fought for justice throughout history. All too often even our Civil Rights lessons are taught in ways that imply that the work of racial justice is only for Black Americans, which leaves White students and other students of color unsure of where they fit and what their role should be. In contrast, fostering a commitment to justice for all students means teaching students about the work of White and Asian activists like Walter Reuther and Grace Lee Boggs, who also committed their lives to the fight for racial justice.

At Justice Leaders Collaborative we strongly believe that schools are the only institution in our country that can create the world we all deserve. Schools do a lot of the heavy lifting when it comes to raising and preparing the next generation. If we are committed to preparing students for a diverse world, a world in which their fates and futures are intertwined, a world committed to equity and justice, then we must take seriously the need to educate in ways that are aligned with these goals. This means using clear Standards of Justice to guide our work. And it means supporting educators in our teacher preparation programs and professional development in doing their own learning and self-reflection so that they are prepared to implement these standards.

View the full the Standards for Justice and download them for for free at: https://www.justiceleaderscollaborative.com/standards-for-justice-k12

Learn more about the full EJATT at: https://www.justiceleaderscollaborative.com/justice-assessment-transformation-tools

Download the Just Books Tracking Tool: https://www.justiceleaderscollaborative.com/just-books-tracking

Learn more about our trainings, workshops, and offerings for educators: https://www.justiceleaderscollaborative.com/for-educators-and-schools

Shayla Reese Griffin is the co-founder of Justice Leaders Collaborative and the author of the forthcoming children’s book An Introduction to Race for Kids Who Want to Change the World (and Grownups Too!) illustrated by Christina O.; two adult books, Those Kids, Our Schools: Race and Reform in an American High School and Race Dialogues: A Facilitator’s Guide to Tackling the Elephant in the Classroom; three Justice Assessment & Transformation Tools for k-12 schools (the EJATT, now available for purchase), organizations (the OJATT), and institutions of higher education (the HEJATT); and lots of medium essays. She is a mother of 3 and coincidentally tends to get her best ideas around 3am.